He was sitting on top of the rocks when they found him, hunched over like a writer might lean into a keyboard. With his left arm tucked into his chest, the Army airman, or what remained of him after six decades atop this California glacier, was wearing a coarsely woven brown sweater. His wavy hair bleached by the sun, he had waited patiently for this moment, his undeployed parachute still at his side.

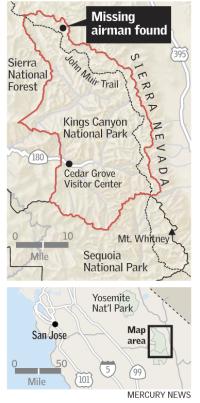

When sunlight glinted off the airman's ring, Peter Stekel stopped in his tracks. The Seattle author had been researching the story last month of a crew of World War II servicemen whose plane vanished in 1942 after taking off from a Sacramento airfield when he discovered the remnants of the 65-year-old accident scene. What Stekel found was a tangle of plot lines - aviation mystery, scientific riddle, and a heart-wrenching drama playing out for six decades in small towns across the United States.

"I thought about this guy's family finally getting closure," Stekel said. "I always thought that was a hackneyed phrase, and it is, until you're in a position to understand what it really means," he said. "My journal from that night says something like 'after 65 years in the glacier, somebody's going to know who you are. You're finally coming home.' "

The case is a forensic replay for military anthropologists now trying to identify the remains. Two years ago, ice climbers had found the frozen body of another one of the four crew members, air Cadet Leo

From DNA to dental records to physical clues like a dried-up leather wallet, "we're letting the evidence speak to us," said Dr. Robert Mann with the Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command in Honolulu, the largest forensic lab in the world. "With no living witnesses, we have to work with 60-year-old pieces of a puzzle and put it together again."

Investigators are all but certain that the mummified remains are one of the three men who vanished with Mustonen when their AT-7 Navigator trainer plane disappeared Nov. 18, 1942. Pilot Lt. William Gamber, and aviation Cadets John Melvin Mortensen and Ernest Glenn Munn, all were in their 20s when they vanished. Though some plane wreckage was found in 1947, the disappearance has haunted their families.

They include mothers and fathers who'd lost their only son and died before knowing what happened; sisters now in their 80s with

vivid memories of the brother who never returned; nieces and nephews who were babies when the plane disappeared, their uncle a smiling stranger behind the scrim of their imagination.'Special gift'

The Mustonens, at least, have their answer.

"It was a special gift to us, not just having him to bury but to learn finally who he really was," said Leane Mustonen Ross of Jacksonville, Fla. Now 62, she hadn't been born when her uncle Leo's plane went down. The discovery of his body gave her the uncle she never knew.

And it was that old tell-tale grin that did the trick. "The first thing they asked us was 'Did your uncle have a gap between his front teeth?' and I said yes. I had a photo that showed it and they had his teeth. Those teeth were the real giveaway."

Friends and family say Mustonen's mother died broken-hearted, never coming to grips with her loss. Marjorie Freeman, 84 and still living near Mustonen's hometown of Brainerd, Minn., vividly remembers her own mother sharing coffee each morning with the missing airman's mom at her Maple Street home.

"It was always the same," Freeman said. "She'd end up in tears. My mom would reach out across the breakfast table and hold her hands and Mrs. Mustonen kept repeating the same thing: 'Oh my poor Leo. If only they could find him and bring him home.' "

Mustonen's mom died years ago, but finding her son's remains has at least brought comfort to those few relatives still around to welcome him home.

"I feel close to him now, as if he'd been a brother," his niece Leane said. "He'd always been cloaked in mystery. Finding him on that mountain made him real."

Just as relatives in 2005 endured the emotional whiplash, the other three families must now go through it all over again.

And only one can get the answer they're longing to hear.

Munn family

Glenn Munn's younger sister Jeanne Pyle, now 87, got the call last month from a reporter in California.

"I thought, 'Oh my, we're going to go through all of this again.' " Still living near the small Ohio farming town where the Munns grew up, Pyle was certain her brother was the man they found in 2005.

"Two years ago, we had so many people coming by - radio stations from Columbus and Steubenville; even CNN flew in from California," she said. "Glenn had blond hair and the one they found encased in ice had blond hair, so we thought for sure it was him."

Once again, the memories are rushing back - the little farm where their dad raised cattle and their mom made cream and butter, the peaches and berries she and Glenn would pick. "The kids all played together, worked together; we were very close and looked out for one another."

Then just like that, it was over.

"Somebody talked Glenn into joining the service in 1942," Pyle said. "He was just a kid, 22, but he was so excited to be going to California. He'd never even been on a plane before, but he wrote mother the most beautiful letters, telling her how excited he was to be learning how to fly."

First came the call that his plane was missing, then word that the search had been called off.

"Mother was heartbroken," Pyle said. "She kept praying he'd turn up alive. She lived to be 102, and she never got through talking about her son, how handsome he was, how proud they were of their first child."

Worst of all, Pyle said, was the not knowing. "Losing a child is terrible enough, but she never knew where he was, and that just leaves a space inside you that you never get over."

Gamber family

Bill Gamber in his youth had been a hero to his younger cousin Dick Christian. Always bigger than life, Gamber in his absence seemed to loom larger still. For Christian, now 82 and a retired associate dean at Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University, the missing cousin was never really far away.

"I'd see some handsome guy who could do everything - straight A's, great athlete - and I'd say, 'There's a guy like Bill Gamber.' He was a guy with an unlimited future; he was smart and articulate and 6-foot-3, and it all just ended. You'd think, boy, what that guy could have done with his life."

Bill Ralston, a musician and retired educator in Cincinnati, was born three years after Gamber's plane went down, but he was named after his uncle and inherited Gamber's beloved silver-plated King trombone, the instrument that inspired Ralston's own musical career.

"Growing up in the little town of Fayette, Ohio, Bill was the All-American boy, captain of the basketball team and a great trombone player," he said. "These were the war years, and my uncle was a symbol of that era. Losing Bill, that whole town was devastated."

Mortensen family

There's hardly anyone left to mourn John Mortensen. With two of his sisters deceased and the third nearly 100 years old with round-the-clock care, it's time once again for his niece Carol Benson to do what she'd rather not do - answer the telephone calls from reporters, fill in what little she knows about her long-lost uncle.

Now 69 and a retired schoolteacher in Ogden, Utah, Benson had lived as a child in Moscow, Idaho, where her uncle was born and raised. She recalls Mortensen being described "as a very compassionate person," but she remembers little else, saying family members were never big on broadcasting their feelings.

"We lived on a farm, and in those years, recovering from the Depression, you didn't have the sort of communication you have nowadays with relatives," she said, "so our families didn't spend a lot of time together."

As a child, Benson was given few details about the plane's disappearance. "I was told he was on a mission and that they didn't return. I remember my mom talking about it when they found the wreckage in 1947. But from then on, they were pretty quiet people who kept things to themselves. I guess everyone has their own way of dealing with loss."

Back in 2005, Benson and her husband, a retired engineer, "didn't want to get involved because we don't like to be in the news; we're a family that doesn't like to talk."

Hope, though, is a hard thing to smother, and "when they did narrow it down to my uncle and Mustonen because they were the same height and (had the same) hair color, then you really start hoping it would be yours."

But it wasn't. So "this time, we don't want to go through that again. We're not going to say anything else until they identify him."

That could still take weeks, largely because investigators are meticulous as they go over the biological, DNA and physical evidence. Though they declined last week to talk about their progress, they did say that having DNA samples from the relatives on the mothers' side of the three remaining airmen will help solve this case much faster.

In 2005, it took them weeks to locate relatives, then obtain samples. And they never did get a sample from Mustonen's family because all the candidates on his mother's side were already dead. Instead, Mustonen was identified by process of elimination.

Asked whether the discovery of a second airman, whose remains were apparently exposed as the glacier receded, increases the likelihood of finding the other two men, forensic anthropologist Paul Emanovsky was guarded.

"You never know what to expect in this job," Emanovsky said. He and his colleagues travel the world recovering remains of service members; 78,000 service members from World War II alone are still missing. "We don't really know the circumstances of this crash. It's possible the other two guys are on the other side of the glacier, a thousand feet away. I suspect they're up there somewhere, but it's hard to know."

Leo Mustonen's niece in Jacksonville knows both the anguish of waiting and the joy of knowing.

"There's a reason this is happening," Ross said. "I think it's a kind of message to everyone who has lost loved ones and never recovered them that there's always room for hope."

Until the remains are identified, though, the three remaining airmen remain frozen in time, in graveyard memorials, and in the distant laughter of the boy on the mahogany staircase in the old Gamber house, or the teenager scaling apple trees in the Munn family orchard, or the Mortensens' young aspiring pilot, heading off forever into the wild blue yonder.

Contact Patrick May at pmay@mercurynews.com or (408) 920-5689.

RSS

RSS